Power & Performance

Those special qualities that separate one aircraft design from another. Performance specifications presented assume optimal operating conditions for the Lockheed AH-56A Cheyenne Two-Seat Dedicated Attack Helicopter Prototype.

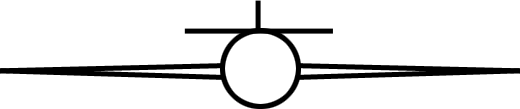

1 x General Electric T64-GE-16 turbine engine developing 3,435 horsepower driving a four-bladed main rotor and three-bladed "pusher" tail rotor.

Propulsion

245 mph

395 kph | 213 kts

Max Speed

25,997 ft

7,924 m | 5 miles

Service Ceiling

629 miles

1,013 km | 547 nm

Operational Range

3,420 ft/min

1,042 m/min

Rate-of-Climb